You don’t name a bike until it names you back.

That’s the rule. At least, it’s supposed to be the rule.

Not everyone follows it.

Those who do? They get what they deserve.

Paint fades, gets chipped or ground off and parts can be replaced, but names?

Names last.

Names are forever.

So, you wait until the machine tells you what it is to be called.

His didn’t whisper it to him. It didn’t hint, and it didn’t leave clues.

The first time it happened, the handlebars twitched while it idled, like a horse shivering off a fly. No wind. No passing truck.

He knew then, but he denied it. That name wasn’t right, wasn’t true, didn’t fit.

They don’t, always.

He didn’t accept it. He gripped harder, fought the twitch, asserted ownership, control, dominance.

He refused the name. Rejected it.

The second time, it was bolder. More insistent.

Final.

The ignition key was still hanging on the pegboard when the engine rolled over in the alley below his apartment, slow and low, like something alive testing its voice.

When he came down, the headlight was already fixed on him. Not the space around him—him.

He swung a leg over. The seat was warm, not from sunlight or a recently run engine, but warm in the way of living things. Beneath the leather, he felt a slow, deliberate pulse.

The throttle didn’t wait for him. The bike inhaled, the revs climbing in a sound closer to satisfaction than combustion. The clutch lever flexed against his fingers as if it were testing him.

He thought he was steering at first, but the streets bent in ways they never had before. Corners rolled up ahead without warning, traffic lights stayed green long past their cycle. He wasn’t riding. He was being taken.

It brought him to the dockyards. Empty cranes sagged against the sky, their cables trailing into black water. The air tasted like rust, oil, and something sweeter, something akin to fruit left too long in the sun.

That was when the cables moved.

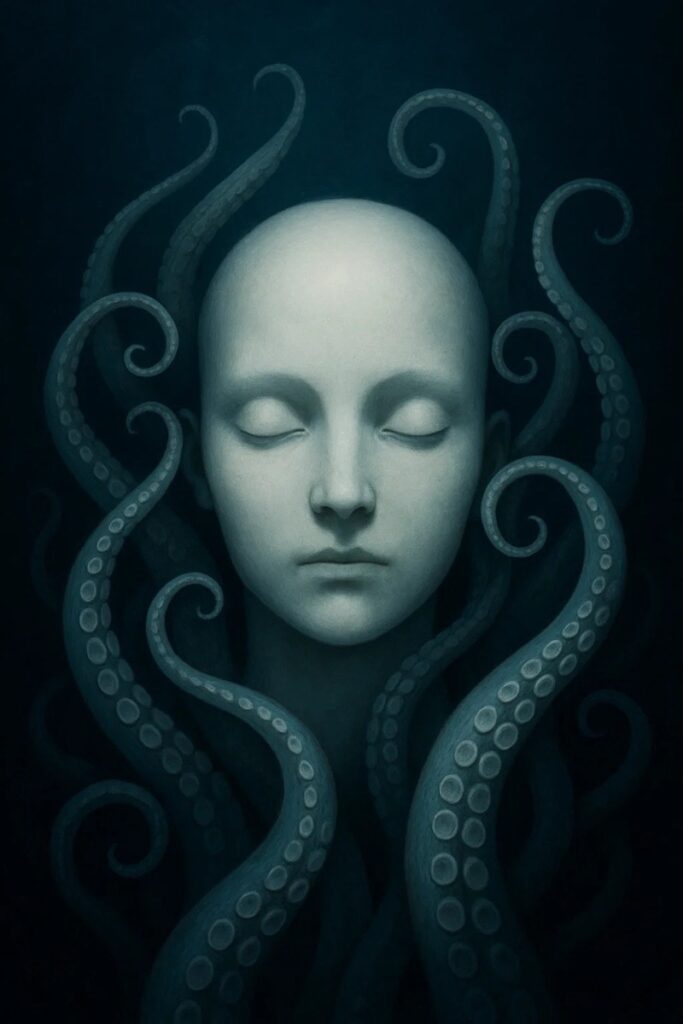

Brake lines split their rubber skins, pale tendrils sliding free and curling around his boots. They pulsed gently, not pulling yet, just being there. More tendrils slipped from the seams in the frame, from the tank, from deep inside the engine casing, warm and faintly slick.

The headlight dimmed, the beam narrowing to a point over the water. Something stirred beneath the surface—shadows uncoiling, patient and huge.

The tendrils climbed higher, tightening slightly, in a way that felt more like possession than restraint.

He felt the answer to the question he didn’t know to ask.

You’ve been mine longer than you knew.

One tendril slid up his spine and settled at the base of his skull. He didn’t move. Didn’t fight.

The headlight went out.

The water broke.

Ownership, possession—neither is a one way street.