(Internal – Compliance Division Eighth Sub-Basement – Access Level: Unobservable)

I. GENERATIVE POLICY CHAMBERS

Employees assume that policies are drafted by committees.

Committees assume they are drafted by legal.

Legal assumes they are spawned in the Nesting Chambers beneath the 8th sub-basement, where the walls sweat ink and the lights flicker in Morse code no one admits to understanding.

Legal assumes this, but doesn’t truly want to know.

Not since The Trevor Incident, anyway.

(The aforementioned incident is not yet formally referenced in any policy, but is the reason that Legal is a) much smaller than it once was, and b) no longer emits policies of its own. They may be assholes, but they’re not stupid assholes.)

These chambers are not on any floor plan. They’re definitely not marked something innocuous like “Office sub-8-17” or “Archival non-storage”. No, that would be too obvious.

Yet all who have worked here long enough? They have passed one.

A door that wasn’t there yesterday, and threatened to open itself for you.

A hallway that narrows as you walk it, its ceiling strangely lower than normal.

A hum, low and menacing, sounding like the sort of printer Gotham’s Joker would buy and laugh at. Or mate with.

Inside the chambers, policies are found—never written.

Some appear handwritten.

Some printed.

Some scratched into metal, or carved into the bases of strangely lifelike balsa wood figures.

Some… pulse. If you don’t watch them closely enough.

All are in revision format.

None have a Revision 0.

No one drafts the policies.

They enter the world already revised.

And every revision is worse.

II. QUANTUM POLICY STATE

Before policies exist, they are felt.

This is known internally as Compliance Uncertainty Principle:

A policy may or may not exist, but you are responsible for knowing which it is before anyone else does.

Before the policy is observed, it both:

- applies to you in full,and

- is not yet applicable.

You must act as though it applies.

You must also act as though it does not.

Both actions must be logged.

Failure to do both simultaneously is considered noncompliance.

Attempts to document contradictory behaviour result in spontaneous policy clarification, a phenomenon where the policy in question manifests instantly—like a serpent deciding which shape to take, based on which prey twitches.

Compliance officers call this Schrödinger’s Policy.

They never say this with humour.

Just the waveform of potential humour.

You know how it is.

Or don’t you?

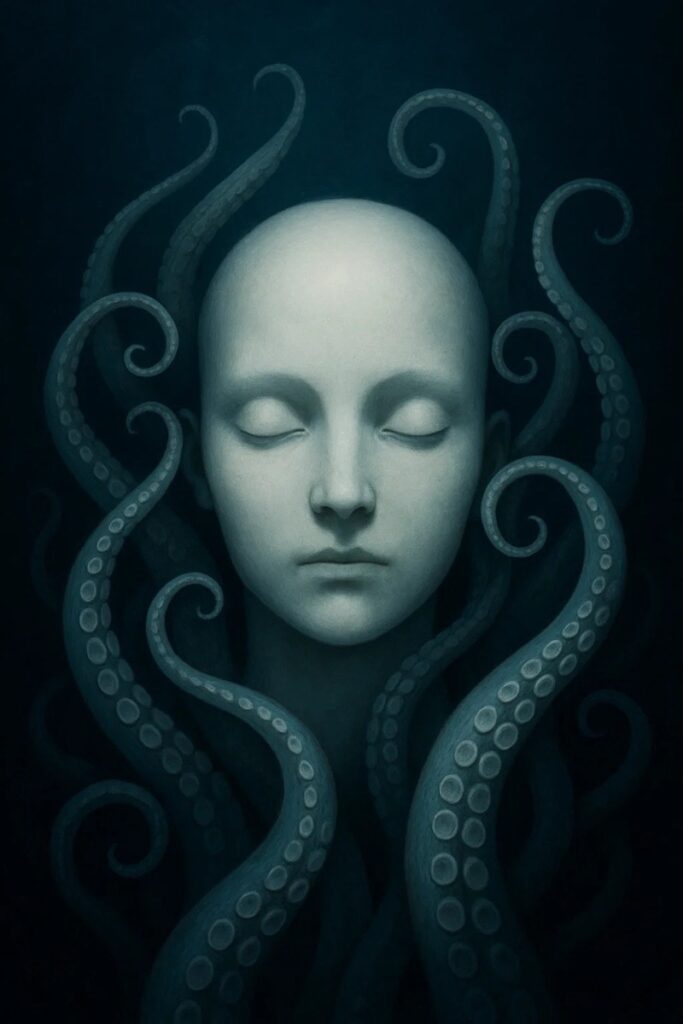

III. TENTACULAR REACH

Policies, once born, extend tendrils into adjacent domains:

- HR guidelines coiling into IT firewalls

- Finance protocols strangling cafeteria contracts

- Parking regulations rewriting procurement orders

- Remote-work clauses that somehow apply to dreams

A policy in one department can force action in another without ever acknowledging jurisdiction.

If traced, the tendrils always lead to a clause that:

- no longer exists,

- has not yet been drafted, or

- technically belongs to a department you have never heard of.

Compliance analysts call these blind tendrils.

They behave like vines reaching for sunlight.

Or fingers reaching for a throat.

IV. POLICY OF THESEUS

Over time, revisions replace every word of a living policy.

One clause amended.

One definition updated.

One term clarified.

One sub-sub-section “corrected in spirit.”

Eventually, not a single letter remains from the document originally adopted.

Yet no one questions whether it is still the same policy.

When asked, Legal offers the mandatory answer:

The policy is its lineage. Not its wording.

But late at night, analysts whisper a darker possibility:

What if the policy is not the lineage at all—

but the hunger that requires lineage to survive?

A living organism replacing its own cells.

A ship rebuilt plank by plank.

A compliance mandate whose body is discarded every quarter but whose appetite only grows.

V. POLICY PARASITISM

Drafts feed on drafts.

A new policy often appears stapled to the remnants of an older one.

The staples are warm.

Feverish.

The older draft is hollowed, as if its contents were siphoned into the new one.

Definitions digested.

Exceptions consumed.

Footnotes emptied like bone marrow.

Analysts refer to this as Policy Infolding, though unofficially many call it policy cannibalism.

No one laughs.

Once a policy has fed, it becomes bolder.

It begins to cite itself.

Then it begins to cite others.

Then it begins to cite internal memos that do not exist—until they do.

The memos appear days later, signed by people who deny having written them.

By then, it’s too late.

Once cited, a policy becomes real.

Once real, it becomes hungry.

VI. THE DRAFT THAT WRITES YOU BACK

Every employee eventually encounters a policy that does not describe behaviour…

…but requires it.

Sentences adjust themselves when read.

Clauses shift based on your pulse.

Definitions expand around the shape of your guilt.

Some employees have reported finding their names embedded in fresh wording.

Not metaphorically.

Literally.

Ink matching their own handwriting.

Signatures they do not remember giving.

Footnotes that seem to comment on their private thoughts.

Compliance assures staff that this is a formatting anomaly.

The formatting anomaly does not agree.

It grows more legible the closer you lean.

VII. FINAL NOTICE

The Policies have no ideology.

No motive.

No agenda.

Only direction.

They crawl forward through committees and workflows and mandatory trainings not because they aim to, but because motion is their nature.

Drafts spawn.

Clauses propagate.

Definitions shed and regrow.

We are not their authors.

We are not their readers.

We are the medium they grow through.

If you feel a policy tightening around your life—

a clause you never agreed to,

a compliance check you never saw posted,

a requirement that feels like someone is whispering it into your ear—

understand this:

Policies do not bind to departments.

Policies bind to people.