He calls her beautiful.

Not in that lazy way men say it to open thighs or doors, but like it’s an act of devotion. As if he’s naming something holy. She flinches every time. In love, she softly offers a soul-deep warning—

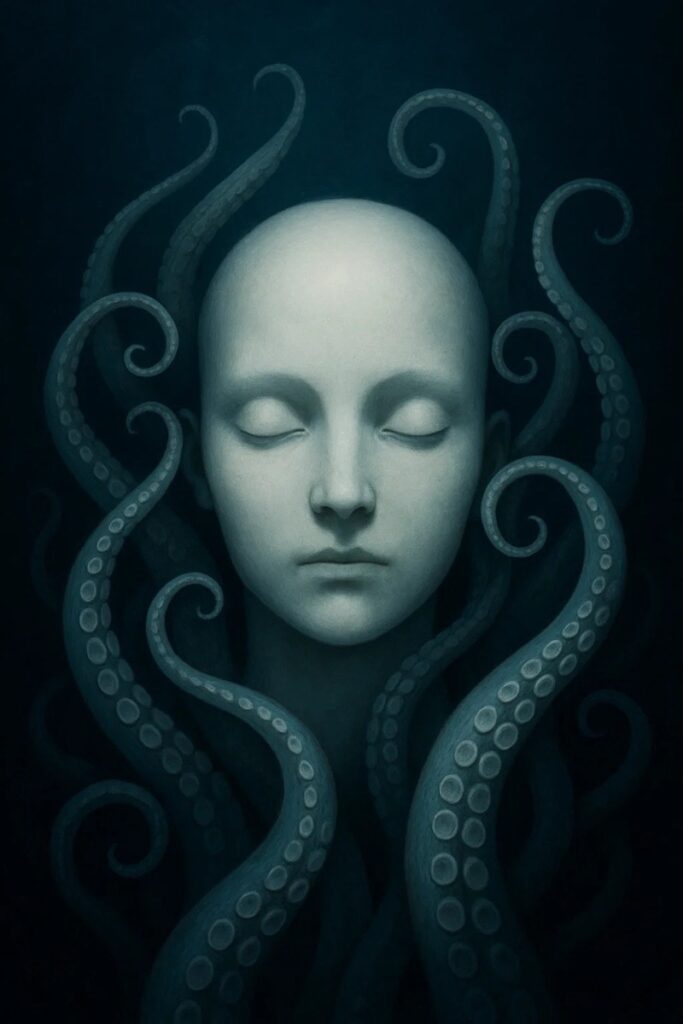

“You will not like what is inside me.”

He thinks she means baggage. Trauma. A few hard years. A series of childhood events, abandonment or the wrong affection. That kind of darkness.

He’s read the books. He knows to stay. To hold space. To be gentle. Forgiving, accepting, not judging.

He thinks she means she cries in the shower.

She does not correct him.

Not yet.

They love quietly. Not passionless—measured. She allows him inside her but only so far, so deep—each time, she wonders how long she can keep him from seeing what else dwells within.

He doesn’t notice the tremors. The way her breath catches—not in ecstasy, but in hesitation.

He’s in the moment.

Distracted from his usual attentiveness by sensation and possession.

He doesn’t know that she sees herself from outside, even now. From the angles learned in shame. From the nights, long ago when she was told she was only worth what she could perform.

He is kind.

Too kind.

He tells her she makes him feel safe.

She wants to scream.

She knows she will hurt him. She can feel the betrayal waiting in her viscera like a knotted tentacle—one with teeth, or maybe claws. She wants to hold him, keep him close; doesn’t want to betray. She wishes she were better than she is. That’s what makes it worse.

The wanting to be other than she is.

She wants to love him cleanly.

Her love is always dirty. Smeared with her history. Soaked in the sodden guilt of every version of herself she was never allowed to be.

He finds a page ripped from a journal once. Just a phrase.

“There are things inside me that do not want to be forgiven.”

He doesn’t ask. She doesn’t explain.

But that night she says it again, not as warning, but as prophecy:

“You will not like what is inside me.”

He tells her:

“I don’t care.”

“I’m not afraid.”

“You can tell me anything.”

She believes him. That’s the problem.

She always believes when they tell her that.

She tells him.

All of it.

Not the details. Never the details. But the hunger she was given. The cruelty she feels like love. The things she’s done in the name of not being left. The manipulations. The lies. The soft betrayals of herself.

He doesn’t leave.

He just goes quiet.

A different kind of quiet.

Later, she finds his toothbrush gone. His drawers empty. A single note on the bed, unsigned.

It says nothing cruel.

Just: I don’t know who that was. I don’t know who I am now.

She doesn’t cry.

She opens her mouth to scream, but it isn’t a scream that comes out.

It’s something older.

Something clawed and soft and shaped like a voice from before she ever learned words.

“You will not like what is inside me,” she says now, to an empty room.

No one hears or cares.

No one ever did.