They always thought she bruised easily.

Like it was weakness.

Like she was soft.

She let them believe it. Let them think she was delicate, ripe for ruin, easily marked and quickly forgotten. But bruises don’t mean breakage. Bruises mean resistance. The body saying: I did not yield. I took the hit. I survived. Fuck you.

Over time, her bruises began to bloom.

Not the yellow fade of healing, but deeper—petal-purples, pulp-blacks, a ripening across her skin. They started to pattern, to take shape and form beyond a mere clotting of blood battered from veins. They began to mean something. Shapes with memory. Veins with volition. Blood, clotted with intent.

The first doctor tried to biopsy one.

It bit him.

A boy tried to touch her thigh at a bar.

She smiled.

When he pulled back, his handprint stayed behind—imprinted, swollen, violet. It lingered for days. His guilt manifested. A new bruise for her collection.

She didn’t even touch him.

Not with her hands.

When he dreamed of her, which he would do often in the years to come, he would remember the smile that started in her eyes and reeked—not of need but of a desire that had nothing to do with lust.

They said she was sick.

They said that her body had turned—betrayed her, split from its nature. She laughed when she heard that. Nature was never hers. It was theirs. Given to her like a borrowed dress she was expected to wear as if it fit.

Her body had other ideas.

The first time the bone pushed through skin, she didn’t scream. She watched. Curious. It was the elbow that gave way first—a pearl-slick nub of calcified hunger twisting its way out like a question mark made of ivory and intent.

It was beautiful.

It hurt, of course. But pain was honest. Pain never lied about what it wanted.

The doctors used words like degenerative, aggressive, autoimmune—like she was a malfunction, a crime. They tried to hide their faces when they looked at her X-rays. One cried.

He was her favourite.

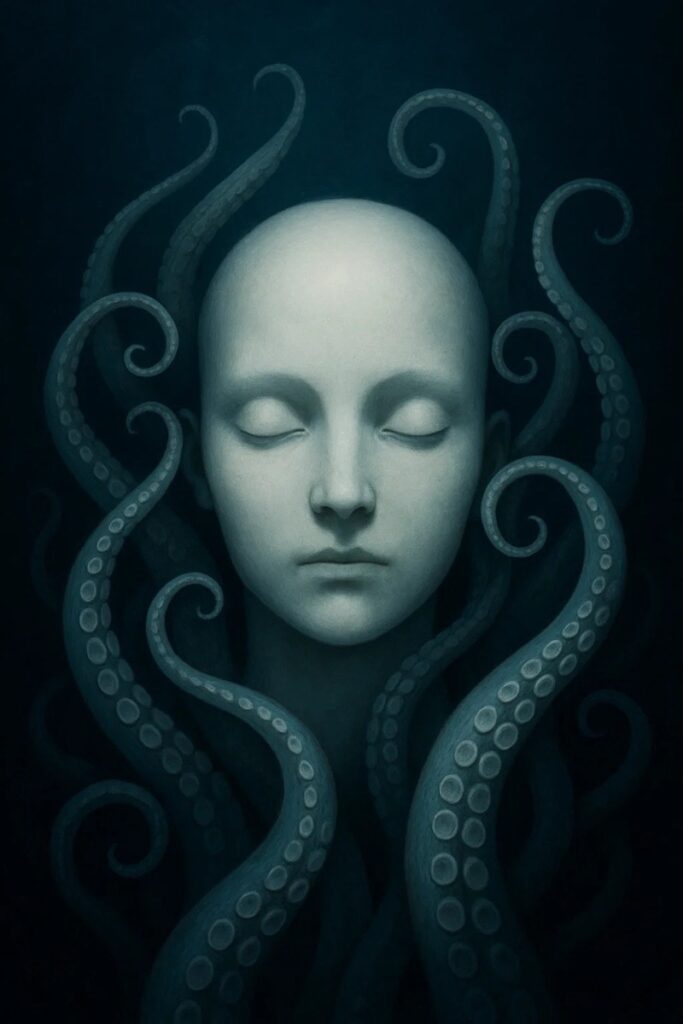

By the third month, she could no longer be photographed. The light didn’t reflect correctly off her anymore. Her eyes absorbed flash. The images came out wrong. Blurred. Doubled. Stretched in directions no lens could name.

She doesn’t shrink anymore. Doesn’t bind, or cover, or apologise. Her jaw hinges too wide now. Her smile has too many teeth, her spine juts like an eviscerated crown, vertebrae lifting into a shape no human was meant to wear.

She’s not meant to be human. She never was.

She walks into rooms and doesn’t flinch when people recoil. She watches their pupils contract as if their minds are trying to shut her out.

She loves their fear.

It’s the only part of them she values.

Once, she was told she had a kind face. That face is gone now—replaced by something that pulses, veined and wet with transformation. Her skin has gone glossy in patches, scaled in others. Her fingers end in suckers or claws depending on the day.

She sings often.

There is no hiding. No shame. No veil. The bruises are permanent now—some green, some purple, some pearled over with a shimmer of something like nacre, something like infection.

She wears them like scripture.

They used to call her broken.

Now they just call her that.

Thing.

She doesn’t correct them.

They are correct.

She is that thing.