In daylight, the cathedral devours sound. A cough ends at the lips, the gasping exhalation silent. A murmured psalm disappears between one heartbeat and the next. No echo, no murmur, not even the whisper of feet across flagstones.

A hymnal dropped slaps the stones without a hint of sound.

Every voice is its own prison; sound reaches only the speaker’s ear through bone; on breath it dies.

The people still enter—because they must. Their God, if she is anywhere, is here, and her right to their worship may not be denied. So, they mouth their prayers into silence, believing that their God’s ears can hear what theirs cannot.

Their faith feels more fragile when shared in silence.

At night, the silence breaks. The cathedral’s doors are barred, the stained glass windows emit no light, yet the walls sing.

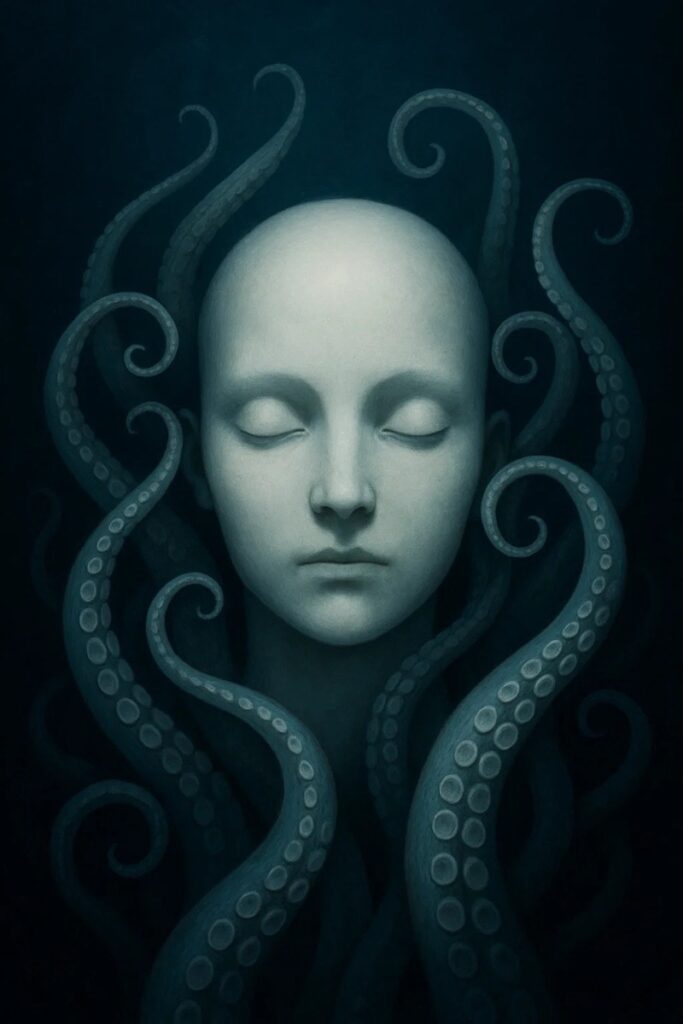

The Cantor exhales.

The first decade it was faint, a chorus like wind through reed pipes, rising only within the nave. The miller’s laugh, once bright, returned as a low drone threaded with grief. The choirboy’s sobs, broken into shards, rose again as a litany in a language no one knew. A dropped basket of donated carrots became a rolling drumbeat, hollow and eternal.

The years passed, and now they listened from the street outside, candles guttering in their hands, tears running as though the inhuman hymn had pried them open. None dared stay inside. None dared ask who—or what—arranges the sounds into such mournful unity.

Now, decades on and the hymn has grown. Not louder. It grew larger.

More voices.

More reach.

Not a radius, not like a circle cast wide across the land—but along a line. A direction. A reaching. Every night the silence spreads further down the valley road, the song extending its unseen hand toward the coast.

The voices do not vanish once sung. They layer. They linger. Every new tone is absorbed, bound to the countless that came before. If you listen carefully—close, dangerously close—you can hear the ones from times long past.

A father long lost to fever, weakly calling his son’s name. He came to his father’s hand then, but now? Now he remembers and tears of loss fall once more.

A child, taken too young, repeating the half-learned lullaby her mother sang. A mother long past mourning, hears and mourns afresh.

Lovers now married hear themselves swearing devotion in voices too young to be remembered. Maybe they smile.

Maybe not.

The living shudder, but they cannot turn away, dare not stop their ears. For who would not stop to hear the echoes of a familiar voice again, even carried on the wind in impossible chorus?

What manner of man would have ears that did not reach for one more hint of his father’s voice?

Night by night, the hymn crawls seaward. Each night it gains—maybe a pace. Maybe five. Each morning, the silence lingers a little longer after dawn.

Some whisper that when the song touches the sea, something long drowned will rise to answer it. Others believe the sea itself is what the Cantor longs to reach—that it will open its vast throat and sing back in answer.

None agree on what will follow.

Some say that the Cantor reaches for what no longer exists.

Maybe they’re right.

What if they’re wrong?