He found the pen in a warped cigar box of forgotten things, the box itself buried behind glossy coffee-table books on fashion and art, all spine-out like sentinels. Beneath them: paperbacks, their pages foxed and swollen with humidity, their covers the kind of lurid that could only be described as necrocilious—a sin of printing best repented for in blood.

“Orric___ __llow __brary __st&fo__d” on the outside of the box.

Inside the box: a rotted hymnal, its pages fused at the corners as though ashamed to open. A moth-eaten bookmark stitched in crude thread, wavering but legible: “Trust in the Lurd.” The U was no doubt a child’s mistake. Or perhaps a truth deeper than the one intended.

And beneath all that, the pen.

Mother-of-pearl. Delicate as bone, but with a weight that suggested burden more than craftsmanship. It gleamed faintly, even in the shade—like it remembered light. Like it waited.

He touched it, and the hairs on his arms lifted like they were trying to pray.

It hummed in a way that only he could hear.

He didn’t think much of it at first. Just took it. Slipped it into his bag like its ownership was already fact.

He was sixteen, or at least that was what he told people. In truth, he wasn’t sure. Dates had a way of feeling hazy. Years had dissolved in sermons and silence. The preacher—his father—had a way of talking that bent time, made it feel as if all moments led back to fire.

He lived quiet. Kept to himself. Said “yes sir” and “no ma’am”. Buttoned his collar even when it chafed. Washed the sin off his hands every Sunday even though he hadn’t done anything to earn it.

The pen changed things.

It started with a name that wasn’t his yet. That was all for the first night. Written on an old gas bill envelope in his bedroom while cicadas rasped outside and the fan turned slow above his head. The ink was too dark. Too thick. It bled through the paper but didn’t spread.

He tried to wipe it off.

It wouldn’t wipe away.

He wrote again the next night. Not because he had anything to say. Just because the pen wanted to be written with.

Soon, it wasn’t just thoughts. It was memories; some of them weren’t his. Confessions, admission of sins he’d never even thought of committing… until now. Truthful things that he hadn’t admitted to himself, and shameful wants, the kind that grew like moss in the corners of the body.

“Her name was Hannah. I didn’t want her. I wanted her voice. Her bones. Her shape. I wanted to be seen the way they saw her. I was inside her and it was nice, but I wanted to inhabit her very being, her life, her entirety.”

He’d never known a Hannah, but he remembered her nevertheless. Remembered wanting to become her.

He didn’t sleep much.

He didn’t pray at all. Prayer seemed strangely surplus now.

The ink marked more than paper. It lingered on his fingers, soaked into the skin. Stained his cuticles. Turned his tongue black one night when he bit his nails.

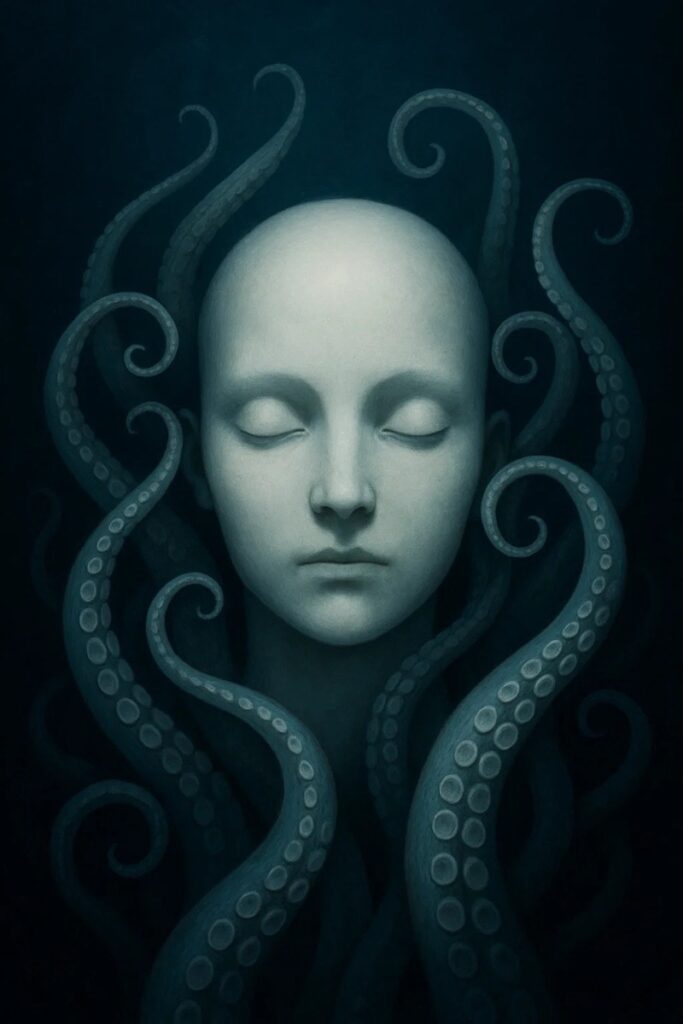

That was the first night he dreamed of them.

Tentacles, but not monstrous and violent—no rape, no forced restraint, not like those in the strange asian comics the boys showed off on their phones, giggling in a way they thought was worldly. No, these were not horrific things. Soft, slow, exploratory and gently curious. They writhed through the slats of his bedroom walls, through the floorboards. They brushed the fan blades, coiled around the ceiling. Never touched him. Not at first.

He met people differently now.

There was a woman in town, too old to be called Miss, too strange to be called Ma’am. Her eyes flickered pale like fishbellies. She sold jars of honey, thick and glistening dark like deep sea oil.

“That pen,” she said once, when he came to her table, “weren’t neva meant for no boy t’ be usin’. Leastways, not for too long…”

He didn’t correct her. She already knew anyway.

She looked at him for a long time. “But maybe it was meant for you.”

A boy came to him later, younger than him by a year or so. Grey-eyed. Freckled and bruised. Too kind. The kind who blushed when their hands brushed.

They kissed behind the old church, where no-one could see.

Nothing burned. No lightning struck. Just the taste of something sweet that wasn’t sugar.

That night, the pen wrote: “I don’t want to be forgiven. I want to be changed.”

His hand trembled at the truth, the pen’s shadow bobbing on the peeling wallpaper.

Or was it nodding?

He met others. Some older. One who had once worn a collar like his father’s. Another who claimed to remember a time when the sea whispered instead of roared. One who didn’t speak at all, but sang into his palm, and left him shaking for a week.

They all had the marks of ink from their own pens, deep in the whorls of their fingertips.

He wasn’t alone.

The pen never ran dry.

He started to see glyphs in water stains, messages in mildew. When he walked barefoot through the bayou, the grass parted, the moss gave way as if greeting him.

The townsfolk began to look past him. Not ignore. Their eyes slid off him, couldn’t stay on him for more than a moment, as if he were already fading out of their lives.

He wrote more and more. Hid the pages in forgotten clothes, beneath the floorboards of the attic. In hollow trees. Beneath loose bricks. Were they hidden, or were they offerings?

He didn’t know.

His father tried to summon him, once. From the pulpit. “You are not what God made. The unmaking of Gods work is Sin.”

The words found him, through the ears and lips of others, but he didn’t answer.

Not in words. In a look over the breakfast neither of them was bold or angry or sad enough to stop having.

He scrapes the blackened crusts against the edge of the plate, and the sound is awful—ceramic teeth grinding on rusted tin.

His father eats slowly, methodically, like it’s penance ritual. The still-a-son eats faster, like he’s trying to get it over with before the weight of their shared quiet chokes him.

The can sits on the table still open, syrup pooling at the edge. The knife they used to dig the lid free rests beside it, sticky and indifferent.

No one speaks. Not because there’s nothing to say. But because what there is to say won’t survive being spoken.

They both gave praise when the meal ended. Not the same way, but still…

He wrote that night until the pen bled from both ends.

When he woke, the bed was slick with ink. Words written on his skin. Names he did not know. A language that hurt to remember.

He walked into the river that morning.

Not to die.

To meet them.

They waited below, soft and old and knowing. Tentacles beckoning, welcoming.

The ink washed from his skin. But not from her soul.

She writes still.

Some nights, if the air is thick and the cicadas loud, you can find a note at the foot of a cypress tree. Damp but legible. The words unfurl like vines, intricate and archaic.

“I am not healed. But I am whole.”